Available in German and English editions in bookstores or on the emanomedia website.

German: https://my.emanoshop.com/merkmale-der-perzeption-und-konstruktion-von-melodien.html

English: https://my.emanoshop.com/features-of-the-perception-and-construction-of-melodies.html

Statement of Aims

Statement of Aims

This book analyses techniques used by both composers and improvisers alike to construct melodies, and examines how these compositional elements correspond to psycho-logical mechanisms in the brains of the listeners.

By dealing with both the perception of melodies and their construction, it becomes clear that this is an interdisciplinary approach. The examination of the perception of horizontal tone sequences is grounded in music psychology based on cognitive science. The examination of the means by which composers and improvisers build melodies touches on music theory, musicology and, of course, composition, and improvisation.

It is explained how the specific melodic features of western music contribute to a high degree of acceptance on the part of the listeners (an acceptance that often lasts decades and centuries), and illustrates that such melodies are in fact works of applied music psychology. It is because of their ability to connect with the complex perceptual mechanisms of the brain that these melodies are so widely accepted.

Compared to other such works which deal with this subject matter, this is both a text book and, in some ways, a musical work book. It provides many more musical examples than a regular textbook, as well as providing more written explanations than a musical work book.

My work is based on studies by outstanding protagonists of music psychology such as David Huron, Carol Krumhansl, Laura Cuddy, Aniruddh Patel, Fred Lerdahl, Stefan Koelsch (and many more scientists listed in the references). However, while their publications work almost exclusively with examples from classical music (Bach, Schubert, Mozart), I focus on music from the other side of the spectrum. By dealing with one piece from the American Song Book and a 4-choruses improvisation by Keith Jarrett (although I do also briefly examine Bach’s “Inventio 4”), this work broadens and deepens the field of research for music psychology, music theory and musicology.

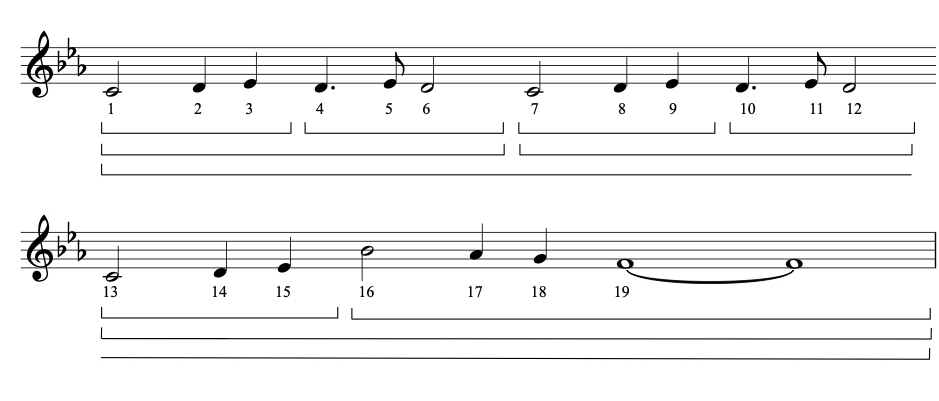

As opposed to most other works in this field I exclusively study three pieces of music over hundreds of pages. There is not a single event in the 90-notes-melody of Richard Rodgers’ “My funny Valentine” that is not discussed from any angle of melodic construction and mental processing. The same pertains to a somewhat lesser degree to the improvised melodies of Keith Jarrett. The reason why I start with the “Inventio 4” of Bach is to show that the melodic constructions of the composer and the psychological mechanisms in the listeners are basically the same in all genres of tonal music in the Western World.

Disregarding rare exceptions, the books of the authors mentioned are on a high abstract scientific level. This book also operates on a scientific level, but does so in a way that allows even less trained readers to understand. This is achieved above all through a large number of musical examples and diagrams. With this book, I not only want the readers to understand how melodies work. I also want to enable those readers who invent their own melodies to use this understanding in their practical musical work. In other words, I want the results of scientific research also to be applicable in practice. At least among the publications known to me so far, there is none that has a similar intention and is conceived accordingly.

Topics of Sections

ORIGIN, OBJECTIVE AND PROCEDURE OF THIS BOOK

I the preface, I describe my own personal motives why I set out to write this book. I am doing this because I believe that for many music listeners there are pieces of music that captivate them, and that they want to know in more detail what the reasons are.

INTRODUCTION TO THE TERM OF MELODY

This section aims to give an introduction to what composers and music theorists have understood by the term of melody in the past. It should not be forgotten that even in the 18th and 19th centuries, very prominent harmonic theories were written, while the statements on the structures of melodies remained very vague, nebulous and often almost mystical. And even if one asks students today what the essence of melodies is, the answers are often similarly imprecise. Since the aim of the book is to provide exact and precise statements, I will begin by providing this small historical overview in a book that aims to lighten the nebulous character of the essence of melodies.

MELODY AND MUSIC IN A PSYCHO – BIOLOGICAL CONTEXT

Here, I provide the larger theoretical frame of reference within which the statements of this book are situated. Melodies as a musical element, which is inherent in almost all musical expressions, are a sequence of physical events which, at least in the western world, are both an expression of the psychological conditioning of the musician and have an effect on the psyche of the listeners. In that melodies as physical events have effects on the listeners’ psyche, they intervene in their biological system, their organism, from the brain to the tips of their toes.

Melodies are music psychology applied by composers and improvisers. Music theory describes what is going on in the musical surface of a piece of music. Music psychology as a discipline of cognitive science explains why melodic operations work. These findings can be helpful for anyone who deals with melodies as a listener or musician.

A major goal of my work is to describe the reasons why melodies are successful. They are so because they respond to the cognitive machinery of the human being, a machinery that is closely related to human emotions and in which tonal music serves as a means of communication that is similar to language in many ways.

MUSIC PSYCHOLOGICAL MECHANISMS IN COMPOSED MELODIES I

After outlining the theoretical framework in the previous section, I begin to apply cognitive science and information theory findings very concretely to two of the three musical examples examined in this book. One is a composition from the baroque, namely Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Inventio 4” and the other is a piece from the American Songbook, namely “My funny Valentine” by Richard Rodgers. I show how statistical learning leads listeners to intuitively determine the tonality of the pieces, to create hierarchies that distinguish important notes from less important ones, and to experience the relationship between tension and resolution. For this examination, as for any other in this book, I will show what the melodic-interval operations that composers have set up in the musical surface consist of, and what mental processes they lead to. In other words, it always involves the perception and construction of melodic events.

MUSIC PSYCHOLOGICAL MECHANISMS IN COMPOSED MELODIES II

In this section, I continue with this approach, but I now focus on the piece “My funny Valentine“, which is not only a well-known work of American popular music, but has also been a jazz standard for a long time. A first focus in this section is to show how composers probably unconsciously use the principles of psychological distance to create emotional effects. A second focus is to illustrate how the Gestalt lawsderived from perceptual psychology find their manifestation in the melodic-interval operations.

MUSIC PSYCHOLOGICAL MECHANISMS IN COMPOSED MELODIES III

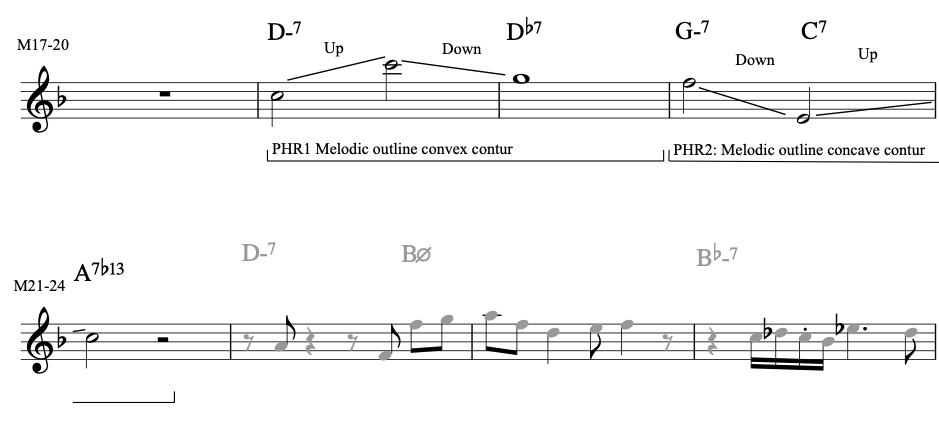

While I talk about the construction of melodic-interval events in earlier sections, this section deals with melodic-temporal operations. On the one hand, basic musical concepts are clarified from a music-psychological point of view, as they are not explained by music theory. This results in important questions such as what the concept of form actually means in its psychological dimension. And form, in turn, is the result of the enormously important mental mechanism of grouping – a concept or mechanism whose importance for understanding and creating melodies cannot be overestimated.

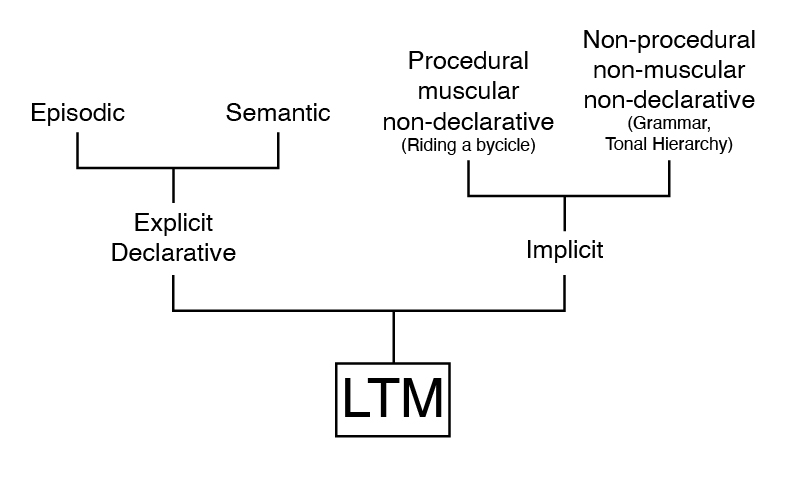

MENTAL STORAGE OF EVENTS

Hearing and creating melodies roughly speaking concerns 3 time levels: past, present and future. In order to be able to identify one or more events of a melody as its climax, we must have at least an approximate memory of which events took place before. At the same time, each sequence of melodic events arouses the expectation of future events. In order to show these connections and their significance for emotions, I present in Section 6 the different forms of storing past events, forms of a kind of absolute present, and how we extrapolate the probability of future events from past events.

Whether melodies can be remembered and how quickly the mental processing of melodic events, the perceptual fluency, takes place, has a great impact on whether melodies are liked or perceived as beautiful.

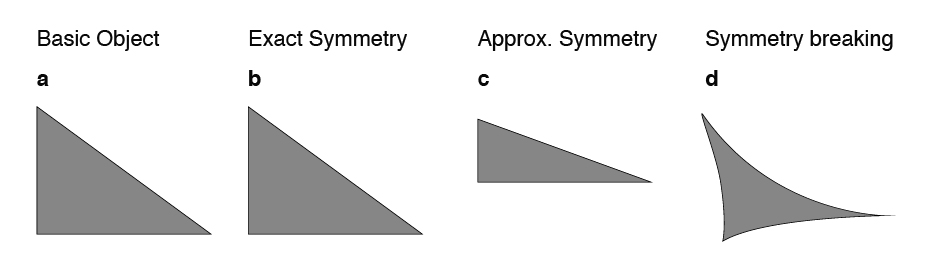

SYMMETRY

Building on the finding that perceptual fluency has a major impact on whether listeners like a melody, it is important to examine which structures in a melody provide for accelerated mental processing. An eminently important candidate for this is the creation of symmetrical relationships. In this section, I not only develop basic components for my own theory of symmetry in horizontal tonal events. I also show, as almost the whole book does, by means of musical examples and diagrams, which symmetrical relations play a role.

CONFIRMATION AND VIOLATION OF EXPECTATIONS

Modern music psychology has recognized the great importance of building up and violating expectations for the emotions of listeners. For this reason, I dedicate this section to this topic and in a certain way continue my explanations from earlier sections. Here, it is important to me to show that listeners expect permanently symmetrical conditions of different manifestations and that the reduction of symmetry is always unconsciously processed as a surprise.

MUSIC PSYCHOLOGICAL STRUCTURES IN IMPROVISED MELODIES

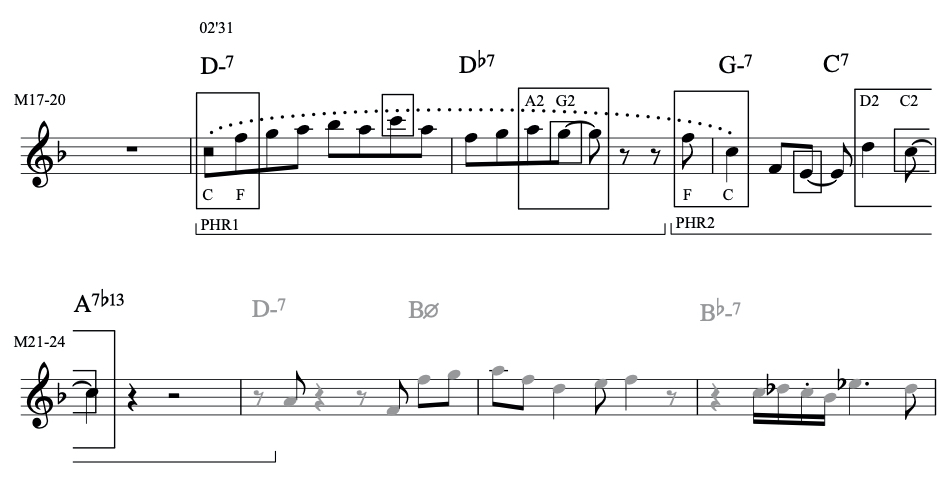

I pursue the approach of the whole book, but this section is now devoted to improvised melodies rather than composed ones. These are the horizontal tone sequences that jazz pianist Keith Jarrett plays over the chord progression of the piece “Too young to go steady“.

Two central questions play a major role here. The first is to ask: what are the melodic strategies with which the build-up and release of tension can be shaped? The second central question is: With which melodic operations is it possible to invent melodies over a period of 6 minutes, which create the impression of a continuous whole for the listeners?

I essentially refer to three melodic strategies and their manifold differentiations. These are the strategies of matching, coherence and cohesion. With the last two terms I build a bridge back to the beginning, where I already talk about coherence and cohesion, which are originally linguistic concepts, namely in the context of music, communication and narrative texts.

Epilogue

The epilogue does not give a summary of the contents of the book. Rather, it gives a preview of what work might follow this book.